It’s the biggest issue in Texas GOP politics right now — and lawmakers’ biggest headache.

Its legal name is ad valorem tax, also known as property tax, and progress toward its elimination is like Schrödinger’s cat: both alive in the air of electoral politics and dead as soon as the box of legislative reality is opened.

Past sessions have halted and inter-lawmaker relations have deteriorated over it. It’s the thing everyone agrees is a problem but nobody agrees on how to solve it, if it even can be.

Gov. Greg Abbott and Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick, the state’s top two elected officials, are already making the issue the centerpiece of their respective reelection campaigns this year. Both have rolled out their plans for further reform in 2027.

Abbott is pining for tax and spending caps, or rollback elections on local governments, constitutionally banning the largest portion of local tax bills, and enacting a more stringent appraisal cap than the one that derailed the 2023 legislative session.

“Just to be clear, if we keep doing the same thing over and over again and not getting a result that the voters want, that’s called insanity,” Abbott told Texas Bullpen in an exclusive podcast interview last week, referring to massive overhauls to the property tax system the Texas Legislature passed in 2019, 2023, and 2025.

Patrick, meanwhile, is doubling down on his preferred homestead exemption focus, including a reduction of the elderly exemption age from 65 years old to 55.

“Governor Abbott and I agree we must reduce local government spending. Last session, Gov. Abbott, Speaker Burrows, and I increased the senior homestead exemption to $200,000, eliminating school property taxes, forever, for the average senior homeowner,” Patrick told Texas Bullpen in a statement, noting that he wants to next eliminate school property taxes for Texans under 65.

“‘Operation Double Nickel’ will expedite that goal by lowering the threshold for the senior homestead exemption from age 65 to 55, freezing 3.3 million home values forever,” he said. “Before becoming Lt. Governor, I fought to reduce property taxes in the legislature. There was little interest. I’m thankful Texas has a governor and speaker joining me in cutting property taxes further.”

For Republicans in Texas, immigration and border security have consistently ranked as primary voters’ top issues for the last few cycles. While those issues are still top of mind for voters according to October 2025 polling from the Texas Politics Project, the rhetoric is now elsewhere for GOP politicians: property taxes.

The Legislature has allocated tens of billions of state dollars toward reducing local property tax bills since 2019 — $51 billion, to be exact, in the most recent state budget.

Despite that — and for more reasons than can be counted on both hands — Republican voters are still not content. That Texas Politics Project poll showed that only one quarter of GOP voters believe the Legislature has done “a lot” to reduce tax bills.

Republican politicians see the same kinds of sentiment in their private polling, hence the focus from Abbott and Patrick.

When asked about the pair’s relationship, Abbott told Texas Bullpen: “Directionally, he and I are on the same page probably all the time. It’s just a matter of the degree or the nuanced detail of policy issues. But you know, policy wise, we seem to be fully aligned.”

Both officials have maintained their cordiality to the public, but the behind-the-scenes competition between the pair is real, along with frustrations flowing in each direction.

Patrick has come out on top each time the issue — and the issue of reforming the issue — has surfaced. In 2023, the lieutenant governor forced two special legislative sessions to extract his desired amount of a homestead exemption increase. And this year, the starting point of negotiations was that a homestead exemption increase would be a central component of whatever the Legislature passed.

The Political Problem

Heading into this year’s election, with affordability on the mind of the American voter, Texas Democrats have focused their messaging on issues such as prices and cost of living.

In 2024, that cut in Republicans’ favor. But this year, the double-edged sword is primed to cut the other direction. Democrats across the country are throwing their electoral eggs into the affordability basket, hogtying Republicans to their president and the cost impact rendered by federal tariffs.

Food prices are 2.6% higher than and energy prices are 4.2% higher than a year ago, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Price Index. Meats, eggs, poultry and fish consumed at home are 4.7% higher than a year ago and non-alcoholic beverages are 4.3% higher.

This is all advantageous messaging for Democrats, including in Texas, who hope to do unto Republicans what Republicans did unto them last cycle.

But it’s not all doom and gloom for Republicans on the issue. The most visible metric of affordability — gas stations, with price signs on virtually every corner — has shown some promise: prices for gasoline have, for the most part, dropped.

According to Triple A, the average gas price in Texas is $2.40, about 30 cents less than a year ago, though that noticeable price drop has not yet really reached South Texas. Only Atascosa, McMullen, and Webb Counties are near or below the statewide average, with the lattermost incredibly important for Republicans’ hopes of flipping Congressional District 28, one of the five projected GOP gains under the new congressional map.

The answer Republicans have settled on, both for primary and general election voters, is to focus on property taxes, an issue that has become a top one for the GOP electorate. The 2022 Texas GOP ballot proposition that called for eliminating all property taxes “within 10 years without implementing a state income tax” passed with 75% support. Polling results from an October survey conducted by Hunt Research and provided to Texas Bullpen, showed that 76% of Republican respondents want to see a two-thirds vote threshold for independent school districts (ISD) to raise rates and would be more likely to support candidates who also support it

With ad valorem taxes squeezing household budgets alongside general inflation, the issue has risen the ranks of importance.

The state’s property tax collected per capita is $2,227, more than double its next closest neighboring state of New Mexico. More than half of that comes from one component: the ISD Maintenance & Operations rate.

That component is a top focus for elected officials when it comes to inching toward total elimination of the M&O tax. Abbott called for it back in 2022, echoing a plan by the conservative Texas Public Policy Foundation to buy the component down with 90 cents of every surplus dollar over a decade. The governor has since to reiterated his desire for the passage of something like this policy at campaign stops.

One of the most ambitious components of Abbott’s plan is to let voters decide whether the Texas Constitution should be amended to eliminate that M&O rate for homeowners.

It’s less clear what specific legislative proposal on this issue could gain support among lawmakers at the Capitol. After all, this is a time for grandiose promises, also known as elections, and not the nitty gritty of policymaking.

Patrick, during a December news conference unveiling “Operation Double Nickel,” a tacit response to Abbott’s own proclamations on the issue, jumped aboard the M&O elimination train — but with a twist: “We are on a path now toward eliminating school property tax for every homeowner in Texas.”

Rather than do it by way of a constitutional amendment, Patrick’s plan again focuses primarily on the homestead exemption.

Jennifer Rabb, president of the Texas Taxpayers & Research Association, one of the foremost organizations that weighs in on the state’s tax matters, told Texas Bullpen in a statement that both plans from Abbott and Patrick would have implications for the state’s property tax system that “are likely irreversible.”

“TTARA will conduct a number of studies this year to provide legislators with clear, credible information about the impact of various proposals on taxpayers, our business climate, and core local government functions such as infrastructure, police, and fire protection,” Rabb said.

It’s not just the top officials brawling over this issue, it’s happening downballot too.

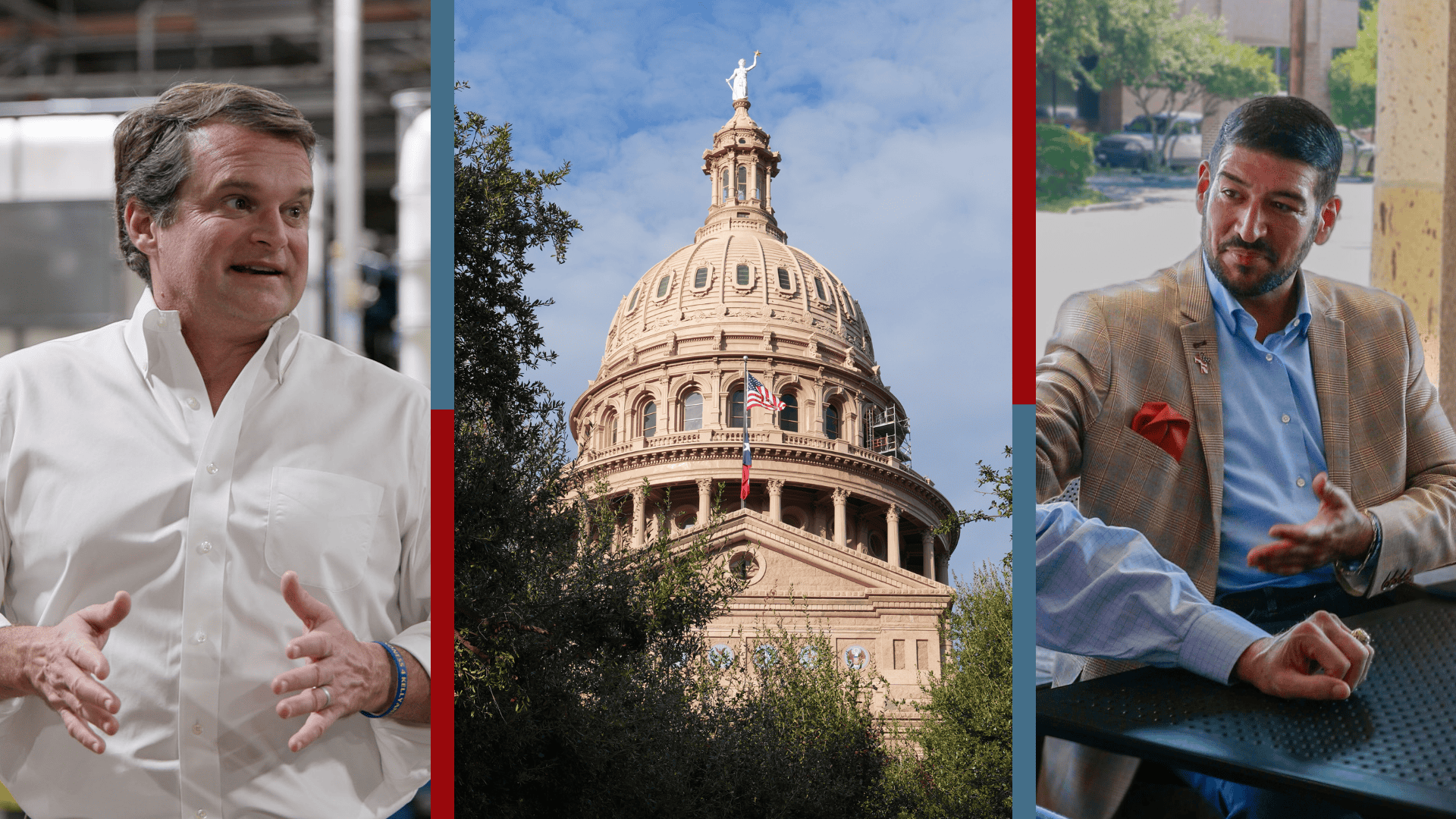

The GOP primary for the open House District 98 seat is, like most Republican contests, featuring property taxes preeminently.

Keller Mayor Armin Mizani is campaigning hard on eliminating property taxes, or “pulling that invasive weed” as he said in a television ad aired last month. It’s the easy and, as most political consultants would argue, the smart position to take for a primary electorate already primed to pine for total elimination.

But his opponent, businessman and Tarrant County GOP Treasurer Fred Tate, has a different opinion.

“I’m personally frustrated with some of the politics around property taxes because we hear over and over and over, ‘eliminate all property taxes.’ And fundamentally, I think you are abusing the voter because you’re not being direct and honest about how you can eliminate property taxes, change the system,” Tate said recently on a podcast hosted by two Tarrant County GOP precinct chairs.

Tate went on to say that his plan parallels Abbott’s slate of reforms while also highlighting a seldom mentioned aspect of this debate. For high-income areas like HD 98 — which, according to Tate, has an average home value of $1 million — a $40,000 increase in the standard homestead exemption, also part of Patrick’s plan, is unlikely to be felt at all when the tax bill arrives.

The competing interests on this issue that flood the state Capitol are more than can be reasonably counted — and it’s not just between the classes of taxpayer, but also between types of district constituents. What maximizes relief in Southlake may not have that same effect in Mexia.

The Math Problem

The entire debate over the elimination of property taxes all centers on the question of how to shift the tax burden from one base to another from residential to commercial, from homeowner to consumer, and from active voter base to less active voter base. It is an unavoidable Sophie’s Choice for lawmakers.

As of the latest available data from the Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts, the estimated total of all ad valorem tax collected by localities in 2024-25 totaled $176 billion; that’s more than the entire General Revenue pot of money, the main part of the state budget.

Of that total, nearly 50% is from independent school districts that includes the debt side of the tax rate. The Maintenance & Operations (M&O) component totaled $60.8 billion, which is still $10 billion more than the amount the Legislature has currently allocated for tax relief.

The governor has trained his elimination rhetoric specifically on ISD M&O rates for homeowners, though some calls for it outside the building go a lot further than that.

No projected data on local levies is available for the coming biennium for an apple to apple comparison.

To buy down the total ISD liability would require $8 billion more than the previous biennium surplus projected by the comptroller at the beginning of 2025. It’s a tremendously expensive prospect.

There is another $28.5 billion sitting in the state’s Economic Stabilization Fund, known as the Rainy Day Fund, but those are onetime funds as they sit there now.

And so, the quandary exists for lawmakers to either spend much of that money now for a one-time reduction in Texans’ property tax bills— not knowing what the next budget cycle will look like and with the prospect of a recession-caused deficit always a consideration —to spend that money in other places, or to let it remain in the fund for the proverbial rainy day.

So far, lawmakers have opted to do some of each, trying to put a dent into multiple problems without solving any of them entirely.

On the flip side, it’s more doable to phase out such a tax over multiple cycles — which is exactly what the TPPF plan calls for — but that requires the existing relief amount to be maintained and for the Legislature to add to it each biennium. It’s a great idea in theory, and if massive surpluses continue, could be possible from a mathematic perspective. But just as there are all kinds of interests trying to pull tax reform in one direction or another, competing interests are all vying for the existing pot of state dollars.

In a state budget process, property tax relief buts up against infrastructure improvements for this booming state, not to mention public education financing, healthcare and research expenditures, entertainment projects, and so much more.

When confronted with the suggestion of eliminating property taxes, Patrick’s continuous retort has been to emphasize that any money left afterward to do other state funding tasks would amount to pennies on the dollar.

Critics of state leadership have suggested eliminating property taxes simply requires the political will to do so. But the political will is only one side of the equation. The mathematical will, and the political dynamics within that budget process, is an entirely different story.

In 2019, legislative Republicans and statewide voters constitutionally banned an income tax, something that had little if any likelihood of materializing; no income tax is a large component for why the growth Texas has experienced has come its way over the last couple of decades. That same year, a proposed one-cent tax swap went down in a blaze of disglory after polling showed how unpopular it was.

But in banning the income tax, the Legislature and state voters removed a potential outlet for future property tax reductions.

Shifting away from property tax and toward an income tax — something that has very little political will behind it — would be inching toward a system that fluctuates with a taxpayer’s ability to pay. If, say, the government shuts down businesses and puts millions of people out of work, those individuals’ tax burden would be commensurate with their income, or lack thereof, in a way that property values don’t move. Some interests pine for such a shift while others would abhor it.

Virtually everyone agrees the status quo of property taxes in Texas is suboptimal, if not entirely unacceptable. But that’s where the agreement stops.

Put another way: The politics of property tax reform is not two wolves and a sheep voting on what’s for dinner. It’s three sheep lassoed together, moving in entirely opposite directions.